Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

A three-part series that tells the story behind one of the largest youth detention abuse scandals in American history.

Almost 1,300 people say New Hampshire failed to act to protect them from child abuse at youth facilities. Here’s what the allegations reveal.

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

A three-part series that tells the story behind one of the largest youth detention abuse scandals in American history.

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

A three-part series that tells the story behind one of the largest youth detention abuse scandals in American history.

This story contains graphic descriptions of abuse. If you have suffered abuse and need someone to talk to, you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-4673. If you’re in a mental health crisis, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 9-8-8.

It also uses scroll-driven animations.

In 1984, an 11-year-old boy, now known in court documents as John Doe #441, said his adoptive father was regularly beating him with a two-by-four.

“I tried to have him arrested for abuse,” Doe #441 told NHPR. “I was pretty much mocked. And that’s when everything started.”

Doe #441 acted out. He ran away. He was labeled a “problem child.”

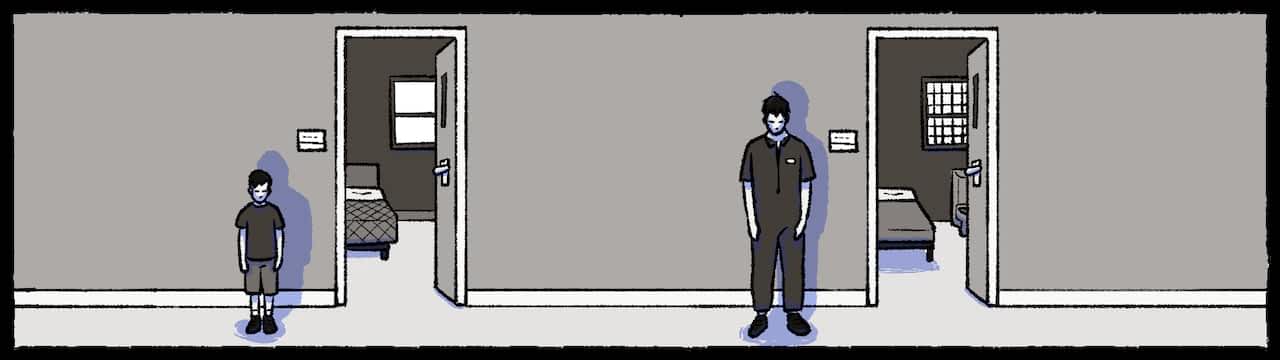

Eventually, he was sent to New Hampshire’s Youth Development Center, or “YDC” – the state’s jail for kids.

YDC’s stated mission was to nurture, protect, and educate Doe #441 – to change him for the betterment of society. In practice, he said YDC was a nightmare almost beyond imagining.

In a lawsuit against the state of New Hampshire, John Doe #441, claims staff at YDC regularly beat him, humiliated him and deprived him of basic dignities, and encouraged violence between residents as a tool for retaliation.

“The guards took hold of his arm and wedged his fingers into the door jamb, while one of the guards slammed it shut. Plaintiff, aware of what was happening, pulled his hand with all his might, but the door caught his small finger, crushing it.”

“They spit in his face, spit in his food, mocked him incessantly, locked him in his room or at a bench staring at a wall for days on end, urinated on his bed, and kept him stripped to his underwear for long periods of time.”

“[The guards] responded by purposely placing the older resident in Plaintiff’s cell where, foreseeably, the older resident anally raped Plaintiff. The staff then spread the word that the Plaintiff ‘liked it,’ meaning enjoyed the rape.”

The list of examples goes on and on.

“They tortured me for years,” said John Doe #441, who is now 51. “I don't like to hate people, but there is so much hate in my life for these people.”

John Doe #441 is not alone.

Since 2020, almost 1,300 people have filed lawsuits alleging they were abused as children at New Hampshire’s juvenile jail and more than 50 privately-run facilities that contracted with the state to care for children.

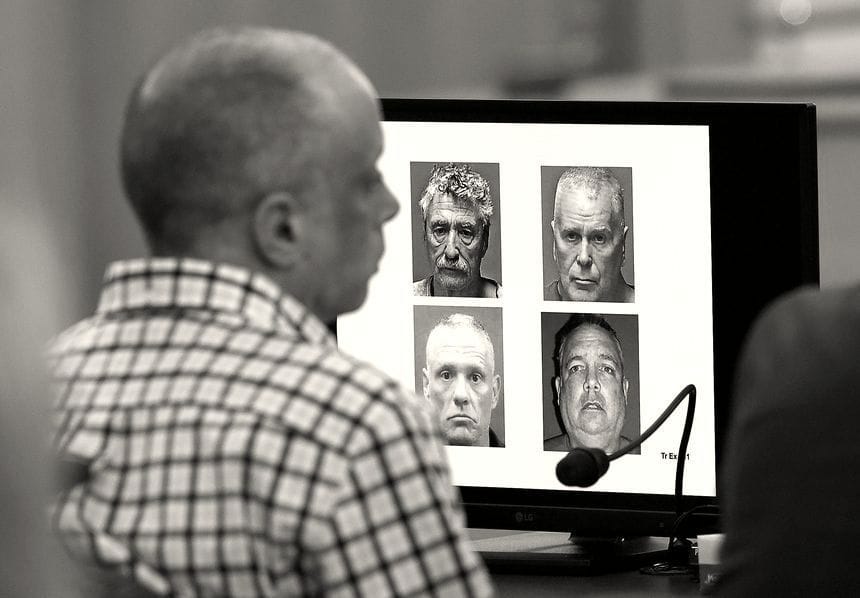

The flood of claims have come alongside a separate criminal investigation by the state of New Hampshire that led to the arrests of 11 former state employees on charges of sexual assault. All have pleaded not guilty.

The allegations span from 1960 to as recently as 2021 – over 60 years. Many of the people bringing these claims forward have waited decades for their stories to be believed – and for accountability from the state. Most have filed suit under Jane or John Doe pseudonyms for fear of stigma and retaliation. They all claim the state failed to act to protect them.

But what exactly happened? How could child abuse of such scale and severity go ignored for so long?

To find out, we read and analyzed 1,281 lawsuits filed by people alleging abuse in state custody. Each one includes a specific account of the abuse each person says they were subjected to as a child.

Collectively, the documents represent the most complete history yet of alleged abuse at New Hampshire’s youth facilities – and they reveal the largest government scandal in New Hampshire, and one of the largest youth detention abuse cases in American history.

Here’s what they show.

Each child on this timeline represents a person who says they were abused at a youth facility in New Hampshire. They are arranged in order of the year they say they first entered state custody.

The volume and depravity of the abuse as alleged in the lawsuits is difficult to comprehend. A review of each plaintiff’s case surfaced, collectively, several thousand detailed examples of abuse.

Along the way, many say they tried to tell adults about the abuse they were suffering. Some children allegedly confided in adults who now stand accused of abuse themselves. Some staff who say they reported suspected abuse claim they were brushed off by management and, in some cases, retaliated against by fellow staff.

Year after year, former residents say, the abuse continued.

In response to the flood of lawsuits, the New Hampshire Legislature established a $100 million fund in 2022 to offer payouts to victims who agree to forgo their civil lawsuit. In 2024, the legislature added an additional $60 million into the fund.

In 2021, state lawmakers also voted to close the Sununu Youth Services Center and replace it with a smaller, more therapeutic and “home-like” facility for up to 18 young people. Officials now expect the new detention center to open in 2026.

The settlement fund and the ongoing criminal probe are acknowledgements by the state government that serious abuses did occur at YDC and other youth facilities.

But at the same time, the state is defending itself against these lawsuits, arguing it was not negligent, and suggesting any abuse occurred at the hands of a “small group of rogue employees, who acted in secret for their own purpose,” as one lawyer for the state put it during opening statements in the first civil trial.

Read NHPR’s coverage of the YDC abuse scandal

YDC was built with a progressive goal in mind: to provide shelter and rehabilitation to children who would have otherwise been sent to adult jail or prison.

But allegations of abuse stretch back almost 100 years.

YDC was built on a farm in Manchester once owned by Major-General John Stark, a hero of the Revolutionary War and author of the New Hampshire state motto: “Live free or die.”

It was created in 1858, in response to what a state legislative commission from the era described as the growing problem of troubled children roaming the streets:

"These boys will grow up sinners, matchless sinners, adepts in every kind of iniquity, thoroughly educated in crime, and hardened to the very core, almost to the obliteration of every moral sense, and at length must end their days in the State Prison or upon the gallows, unless some effort is early made to reclaim them."

Originally called the House of Reformation for Juveniles and Female Offenders Against the Laws, the facility has since been known by several names: the State Reform School, the State Industrial School, and the Youth Development Center (YDC). In 2006, it was rebranded as the Sununu Youth Services Center, after former Gov. John H. Sununu, though many still refer to it as “YDC.”

Throughout its history, those in charge of YDC saw the institution as carrying out a noble mission.

As the trustees put it in 1879, YDC was a “place of reform, and not of punishment; [meant] to save and restore, and not to inflict pain.”

Over the years, New Hampshire courts would send thousands of children to the jail for a wide range of behaviors: from violent crimes to shoplifting to habitually skipping school.

In 1953, 61% of boys were there for stealing; 79% of the girls for “sex misdemeanors.”

A more recent state report with data from 2016 to 2020 shows 75% of all charges filed against youth detained in the facility were for misdemeanor crimes.

But despite rosy annual reports describing rehabilitation and care for children, allegations of abuse occasionally bubbled to the surface.

In the 1930s, the then-governor of New Hampshire accused the facility of using "punitive methods [that] savored of barbarism and the Dark Ages." According to his account, adolescent girls were being whipped with rubber hoses and were sometimes held in almost pitch black “dungeons” for weeks at a time.

Six decades later, in 1994, newspapers reported on the allegations of a 16-year-old boy who claimed he was locked in his room for three weeks at YDC – even during a fire drill.

In 2000, the state launched an investigation into YDC after what state officials described as a “spike in the number of problems reported there.”

YDC staff denied there was any abuse.

“That stuff does not take place. It’s not tolerated,” said Bradley Asbury, who was then a YDC house leader and president of the union chapter for YDC employees, in comments to the New Hampshire Union Leader at the time. “We don’t have time to abuse them.”

Asbury is now charged with acting as an accomplice in the sexual assault of a child at YDC in 1997. He has pleaded not guilty.

Meanwhile, in 2000, the head of YDC insisted it was safe for children, noting that judges continued to order three to four kids to the facility each week. “The judges wouldn’t do that if it was unsafe,” he said.

By the next year, the state declined to release a report from that investigation, but it did announce its findings: five incidents of abuse, all related to excessive force during a physical restraint. One administrator said the incidents didn’t involve what comes to mind when people think of abuse and neglect. A prosecutor at the state attorney general’s office said their impression was that it was a very small group of problem employees. The employees were not identified.

Ten years later, a 2010 report by the Disabilities Rights Center, an independent watchdog group, revealed “a pervasive pattern of inappropriate restraints and excessive use of force by [YDC] staff during the time period reviewed… and a deep-seated and pervasive culture of the use of force to control residents.”

By 2020, the first of the lawsuits captured in this database was filed.

John Doe #441 says when he was at YDC, from 1984 to 1991, staff ran the facility “like the Gestapo,” dealing out brutal punishment for even the slightest infractions.

But according to him, there was an exception: a staffer named Karen Lemoine.

“There really was no training,” Lemoine told NHPR in an interview. “I wasn't told anything other than, ‘Here's the key and it works for every door in here.’”

Lemoine worked at YDC from 1989 to 1991. She had previously worked in law enforcement and corrections in Massachusetts.

Early on, Lemoine says there were hints of a toxic work culture at YDC.

Lemoine worked the overnight shift at YDC, where one of the main responsibilities was to check in on the kids as they slept in their cells. Every 15 minutes, Lemoine was supposed to turn a key in a “watch clock” at one end of the building she worked in – a way for management to ensure the bed checks were performed as instructed.

But one night, she says her coworkers told her: “Don’t hit the clock.”

“But I would just go do them anyway,” said Lemoine, who feared losing her job if she didn’t perform the bed checks. “And there were several times I would be walking down the hall and they would just come up to me screaming at me, so mad at me, where I thought, ‘Wow, he's going to hit me.’”

At the time, Lemoine says she did not understand why her colleagues were so adamant. Later, she learned they had tampered with the watch clock to avoid having to check on the children. NHPR has independently confirmed YDC staff were tampering with the watch clocks as Lemoine described. At least one employee was fired after management discovered the practice.

Lemoine remembers John Doe #441.

She said she first learned about him by reputation.

“He was supposedly the most suicidal and dangerous kid in the place.”

Lemoine said other YDC employees routinely joked about John Doe #441’s suicide attempts, which Doe #441 says began after he was raped by another resident.

Suicide & Crisis Hotline If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call or text 988.

“The guys would just laugh about it,” said Lemoine, “loud enough for the whole tier to hear.”

According to Lemoine, one night she was transferred to the building where John Doe #441 was detained. When she arrived at his door for a bed check, she says she found another YDC staffer, who was not assigned to that building, bent over at the base of the door to Doe #441’s room.

“It just looked to me like there was some exchange between the two, through the door, the bottom of the door,” said Lemoine.

Lemoine said she reported the incident to her superiors, but was brushed off.

John Doe #441 told NHPR there was something passed beneath the door to his room: a razorblade. According to him, it was part of an ongoing campaign by some YDC staff to encourage him to follow through on his suicidal thoughts.

“They'd knock on my door, and then I'd hear [a sound] underneath the door and it'd be a razor blade,” said John Doe #411, who claims this happened on multiple occasions.

Lemoine says the next night, she was working in a different building when she saw the nurse go sprinting by.

“She said [John Doe #441] had attempted suicide with a razor. A small safety razor,” she said.

As John Doe #441 recovered, Lemoine said the jokes among staff about his suicide attempts resumed.

“At that point, I was scared,” said Lemoine. “I realized I was working in the wrong place.”

Lemoine testified as a witness in the first YDC civil case brought by David Meehan. She told the jury she reported signs of abuse to management on multiple occasions, but her supervisors rebuffed her.

She said this included moments where she had filed written reports in a complaint box that were then read by supervisors.

“On more than one occasion, they took them, crumpled them up in front of me and then threw it at me,” she said.

Former YDC Superintendent Ronald Adams disputes the characterization of a toxic culture at the facility.

In an interview with NHPR, he claimed he always took allegations of abuse seriously.

“When we discovered it, we took some kind of action,” said Adams, who worked at YDC from 1961 to 2001.

“I never let anything like that glide by.”

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

Hear Karen Lemoine’s story, including the retaliation she says she faced for speaking up.

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

Hear Karen Lemoine’s story, including the retaliation she says she faced for speaking up.

The stories of alleged victims and former YDC staff point to a long-running culture of abuse and secrecy at the facility.

Certain staff were allegedly able to abuse children for decades with impunity.

Former YDC staffer Frank Davis is named as an abuser by 114 different people from 1972 to 1999 — more than any other former staffer named in the lawsuits. He was one of the 11 former employees facing criminal charges. However, a judge dismissed the charges against Davis after he was found not competent to stand trial.

undefined

undefined

Lucien Poulette is another former staffer facing criminal charges for rape. The earliest allegation against him comes from Jane Doe #79, who claims that in 1977, she was sent to YDC for running away from home – to escape Poulette.

“Plaintiff ran away from home to escape her sexually abusive babysitter, Lucien Poulette.”

Another plaintiff, John Doe #250, says he was also abused by Poulette thirty years later, in 2007.

“Staff member Lucien Poulette anally and orally raped Plaintiff.”

In total, 100 people name Lucien Poulette as an abuser, the second-most of any former YDC employee accused of abuse. Poulette has pleaded not guilty to criminal charges. He declined comment for this story through his attorney.

undefined

undefined

Another former staffer now cooperating with attorneys for the alleged victims, known pseudonymously in court documents as Bonnie Boe, says Frank Davis and Lucien Poulette were among a group of “violent” YDC staff who intimidated well-meaning employees into silence and inaction.

According to court documents filed by lawyers representing the alleged victims, Boe spent at least part of her employment at YDC in the 1990s and witnessed rampant abuse by her coworkers. Her account includes staff beating children “until blood was everywhere,” an employee who routinely masturbated at his work station where residents and other staff could see, and superiors instructing her to falsify records.

Boe claims that after filing repeated complaints with YDC management, her colleagues retaliated against her.

According to Boe, she left work at YDC one day to find her truck “spray-painted with the words “N**** Lover!” Boe’s partner was a person of color, according to the court document.

In another instance, Boe claims other YDC staff removed the lug nuts from her truck, “causing the wheels to fall off” as she drove. This incident is corroborated by an internal YDC memo.

Nine former staff now face criminal charges, including Poulette, Jeffrey Buskey, Stephen Murphy, Bradley Asbury, James Woodlock, Trevor Middleton, Jonathan Tracy Brand, Stanley Watson, and Victor Malavet. Former YDC staffer Gordon Thomas Searles died while awaiting trial. Another former staffer, Kirstie Bean, pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting a teenager and telling him to lie to police about it in 2018.

However, they make up just a fraction of the more than 300 alleged abusers named in the lawsuits. Our analysis shows at least 54 alleged abusers have been accused by five or more different plaintiffs.

According to an analysis by the Associated Press, there are more than 200 allegations of abuse that could be eligible for criminal prosecution because they fall within New Hampshire's statute of limitations for sexual assaults involving children.

Records from YDC are generally not accessible to the public because of laws meant to protect juvenile privacy. But former residents can request their own resident files: Those are collections of reports written about them during their incarceration at YDC.

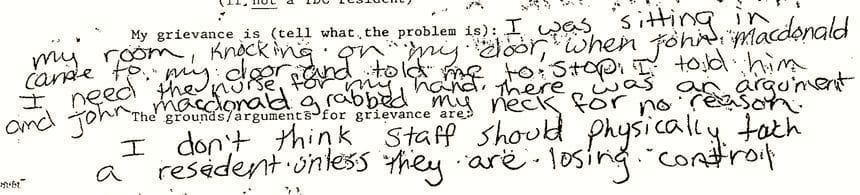

One former resident, Andy Perkins, agreed to share his resident file with NHPR. The nearly 500 pages offer a rare glimpse into the inner workings of YDC, including how staff now accused of abuse documented incidents of violence.

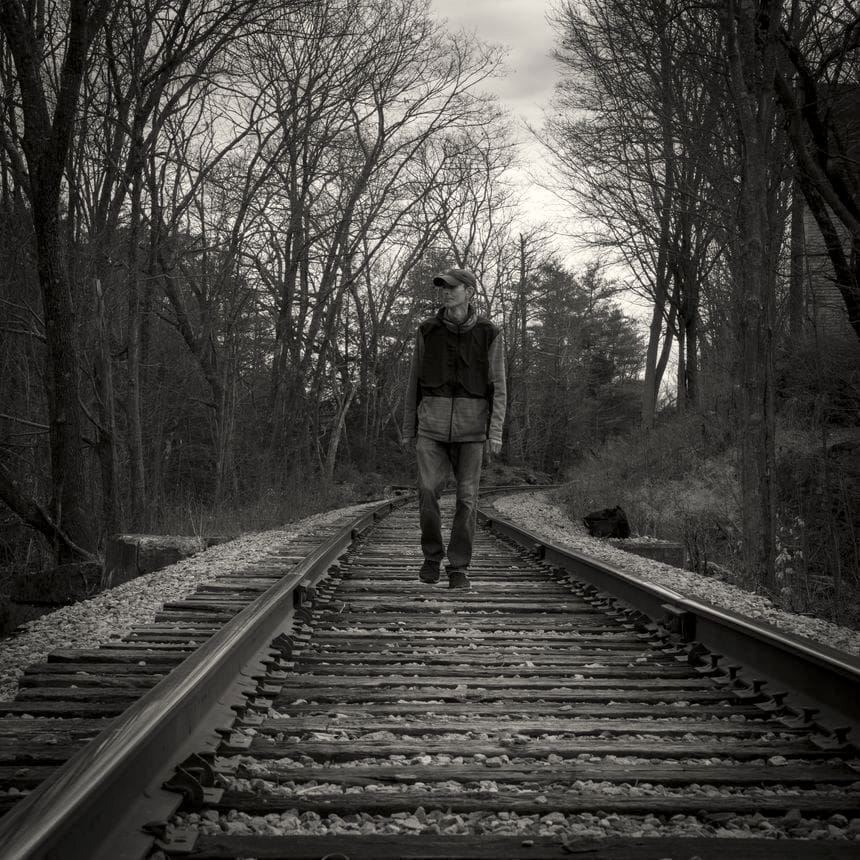

“What really, really, really slammed me was seeing my picture…,” said Perkins. “In the very first picture, I was still OK. I could see it in my eyes, I was still a kid. But not after that.”

Perkins is not among the people who have filed lawsuits against the state. Instead, he filed a claim with the state’s YDC Settlement Fund – established by state lawmakers as an alternative to civil litigation.

By April 2024, more than 400 people had filed claims with the fund. Many of those people had originally filed lawsuits that are contained in this dataset, making it difficult to know the exact number of people claiming abuse.

According to Perkins, he filed his claim with the settlement fund in October 2023. One of the episodes of abuse he claimed was memorialized in his resident file.

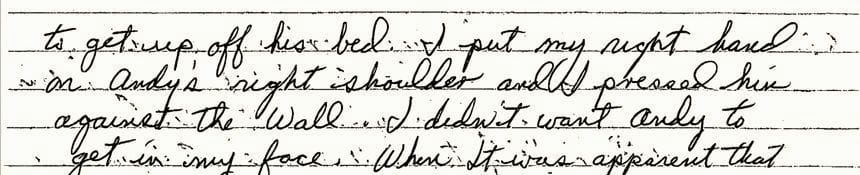

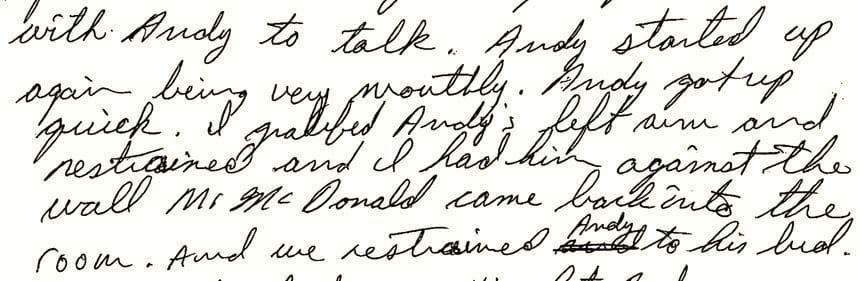

On June 21, 1993, YDC employees John McDonald and Tom Searles described in separate reports an incident where they physically restrained Perkins, who was then 17.

Their written reports are contradictory and full of euphemistic terms for violence.

Searles writes that he restrained Perkins because he was threatening staff: “Andy got up quick. I grabbed Andy’s left arm and restrained and I had him against the wall. Mr. McDonald came back into the room. And we restrained Andy to his bed.”

In McDonald’s account, there were two separate restraints in separate rooms. In the first, McDonald writes, “Andy’s temper was starting to escalate, and I thought he was going to get up off his bed. I put my hand on Andy’s right shoulder and I pressed him against the wall. I didn’t want Andy to get in my face.”

The second restraint, according to McDonald, happened after he and Searles had moved Perkins to another room.

“I left, followed by Tom Searles. When I was about halfway down the hall I saw Tom return to Andy’s room and I followed,” writes McDonald. “When I arrived Tom had Andy in the corner, pressed against the wall. We both guided Andy to the bed and placed him on his back on the bed. We just held him there until Andy calmed down and got a hold of himself.”

Perkins says the truth was much more violent. In his account, after he talked back to the two staffers, they pinned him on his bed with his neck against the wall. According to Perkins, McDonald then grabbed a pillow and put it against Perkins’ neck with his hand around his throat. Perkins says he heard a pop and then went unconscious.

“It was so strange to be attacked like that, just for words. And they were just so ready to,” said Perkins. “I can remember their breath and everything, screaming in my face.”

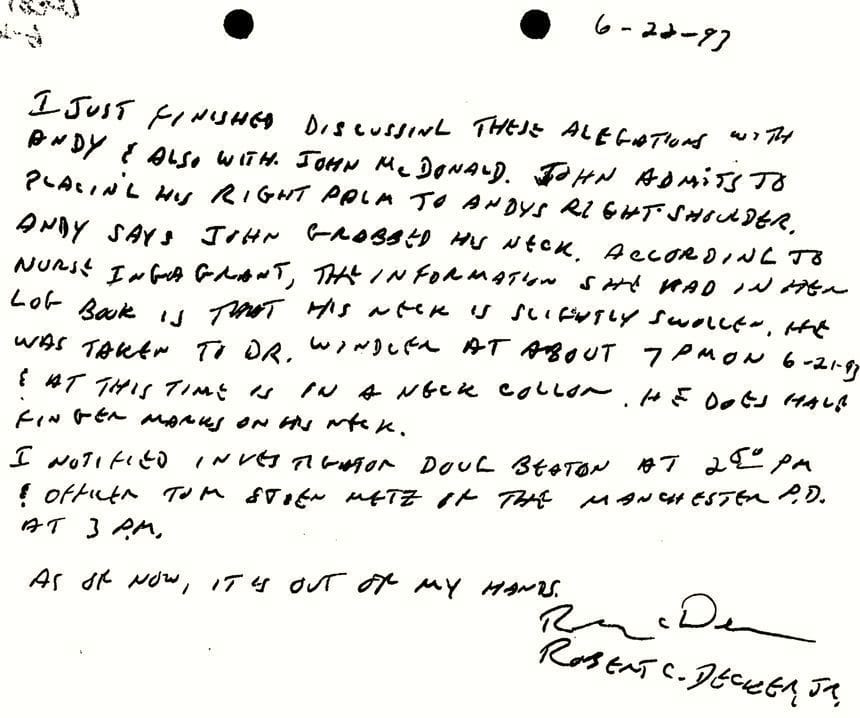

Perkins’ account is corroborated by the report of a third YDC staffer, Robert Decker, written the day after the incident. Decker writes, “He does have finger marks on his neck.”

Decker also writes that he notified local police of the incident: “As of now, it’s out of my hands.” Perkins says local police did speak with him, but nothing came of it.

All three staffers – McDonald, Searles, and Decker – are now named as abusers in the civil lawsuits. McDonald died in 2010. A voicemail left on a phone number listed in Decker’s name was not returned.

Searles was also criminally charged for sexual assaults that allegedly took place in 1995, two years after the incident with Andy Perkins. Searles, who had pleaded not guilty, died while awaiting trial in July 2024.

Perkins says he still suffers from back pain and migraines stemming from that incident. He filed his claim with the settlement fund in hopes he will get enough money to undergo a surgery that may help his condition.

He is debating how much of this story to share with his daughter, Addison, who is now 15.

“She really hasn’t had to suffer, you know what I mean?” said Perkins. “That’s awesome, that’s good. She’s never had to feel poor. She’s never had to feel any of that. Dream come true to me.”

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

Hear Andy Perkins tell his story publicly for the first time.

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

Hear Andy Perkins tell his story publicly for the first time.

The impacts of the alleged abuse are wide-ranging and continue to this day.

Many alleged YDC victims say they ended up turning to drugs for relief from their trauma. Some would go on to commit crimes and be re-incarcerated in adult jails and prisons – the very system YDC was supposed to help them avoid.

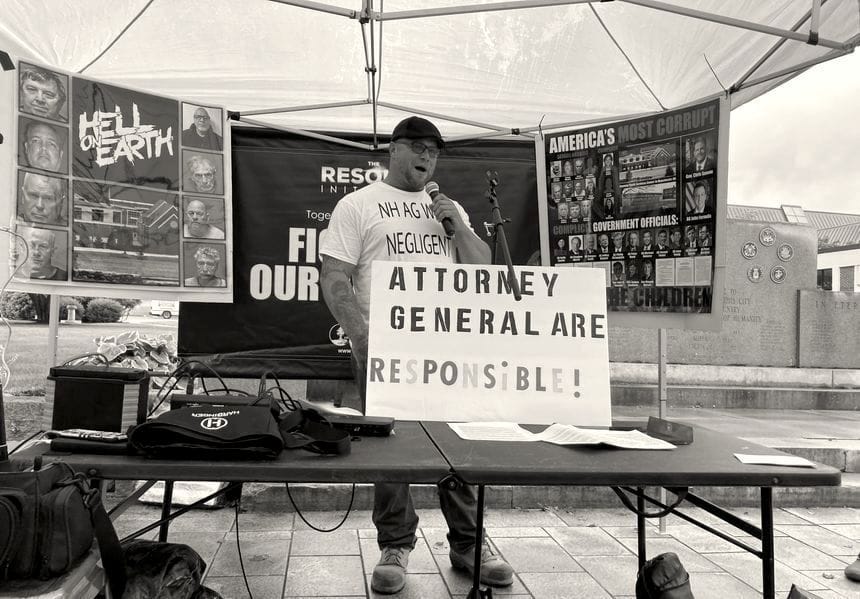

John Doe #612, who has chosen to publicly identify himself as Jason Peters, says the abusive environments he experienced at YDC and another state-run facility raised him to be antisocial.

Peters says beginning at 13 years old, he was regularly beaten, body-slammed, and choked by state employees.

“There was this hypocrisy in what we were told to do on our part. Like, ‘You cannot be violent, you cannot be aggressive,’” Peters told NHPR, “‘but we can do whatever the hell we want to you.’”

“As a kid… you end up just saying, ‘F*** you. I don’t trust you,’” said Peters. “And that becomes a mentality you have towards the whole system and any authority you come across.

“It’s an ironic thing when you’re in a criminal system and the biggest criminals in the system is the system.”

Peters was released from YDC in 1995 at age 17. By 1996, he was charged with murder.

Peters stabbed and killed 25-year-old William Huard of Laconia during a fight, according to a newspaper account of court proceedings. Peters pled guilty to manslaughter and expressed remorse during his sentencing. He spent 18 years in prison and is currently on parole.

If Peters successfully completes his parole sentence, he will have been in the legal system from ages 13 to 47.

“The mentality of being able to take the law into my own hands was taught to me through YDC,” said Peters. “These facilities that they have… it’s failed. Our whole prison industrial complex is a failure.”

In May 2024, a jury awarded $38 million in damages to former YDC resident David Meehan. Meehan was the first person to file suit against the state, inspiring the hundreds of other lawsuits that followed.

His attorneys called it the largest civil jury verdict in the history of the state, though the actual amount could be severely limited by a state law capping damages against the government at $475,000 “per incident.” The issue is still being litigated.

Following the verdict, the judge in the case, Andrew Schulman, dismissed a motion by the state to set aside the jury’s findings. Schulman wrote the state’s negligence and failure to protect Meehan had been proven to a “geometric certainty.”

Schulman added: “YDC leadership either knew and didn’t care or didn’t care to learn the truth.”

During the trial, Meehan claimed the state’s negligent oversight of YDC allowed him to be raped and beaten by staff hundreds of times. His attorneys called several former YDC employees to the stand, including Karen Lemoine. They described a violent culture where management instructed staff to never take the word of children over employees; where some staff wore stickers saying “no rats;” and where nepotism was common.

One of those witnesses was a social studies teacher who said she reported suspected abuse of Meehan and several other children to YDC management and to the state’s child protective services, with no response.

Justice for the full sweep of alleged abuse at New Hampshire’s youth facilities looks different, depending on who you ask.

Some alleged victims want retribution.

“Justice in my eyes? If they were all dead,” said Andrea Martin (Jane Doe #65), who entered state custody when she was 9. “I would like to personally line them up and shoot them dead through the f***ing head. That’s how I feel. I’m sorry if that’s too graphic, but that’s my honest opinion. And then, I would sit down and have a steak and potatoes and have a better life, to be honest.”

Andy Perkins says he tries to resist thoughts of revenge, but acknowledges it is a struggle.

“I want to forgive them, but I can’t,” said Perkins. “I want to, but I know I haven’t.”

In March 2024, the state of New Hampshire paid Perkins to settle his claims of abuse. According to a friend, Perkins has been giving much of the money away to people who helped him in his life.

“The money doesn’t feel like justice, no. None of it feels that way because of how long it went on,” said Perkins. “But knowing that people know it happened – that’s good. It’s going to have to be good enough.”

John Doe #441 pointed to the irony that a legal system meant to teach him about accountability is now facing its own lesson in consequences.

“I paid for what I did in my life,” said Doe #441. “I did 23 years in prison. I paid for it – why can’t they?”

Others, like John Doe #141, shared hopeful visions of what should happen to the land where the YDC buildings still stand.

“They should just tear that whole place up, and build some living houses,” said Doe #141. “Let families take that pain and bury it. Make a nice community of kids, a nice park for kids. Something that represents us, but in a happy way. Something that basically says, ‘They got peace.’”

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

How the widespread abuse at YDC finally came to light and how people are grappling with what justice and accountability even mean in a scandal so large.

Listen to the podcast The Youth Development Center

How the widespread abuse at YDC finally came to light and how people are grappling with what justice and accountability even mean in a scandal so large.

The information below was extracted directly from civil complaints filed by the plaintiffs. NHPR has not independently verified each claim. Some plaintiffs may withdraw, or have already withdrawn, their complaints if they opt for the state’s YDC Settlement Fund or for other reasons. We have redacted the names of the accused except in cases where they have been criminally charged. Download the data.

Editor's note: This story was updated on August 5, 2024 to reflect that Gordon Thomas Searles has died.